- Статьи

- Culture

- Walking as a couple: Valentin Kataev and Evgeny Petrov between the reefs and shoals of politics

Walking as a couple: Valentin Kataev and Evgeny Petrov between the reefs and shoals of politics

In the combined biography of two brothers, Valentin Kataev and Evgeny Petrov, Sergei Belyakov focuses on the socio—political and historical context in which his characters lived (and sometimes were on the verge of life and death), as well as on the equally fascinating household and financial component of the successful career of the Soviet writer. Critic Lidia Maslova presents the book of the week, especially for Izvestia.

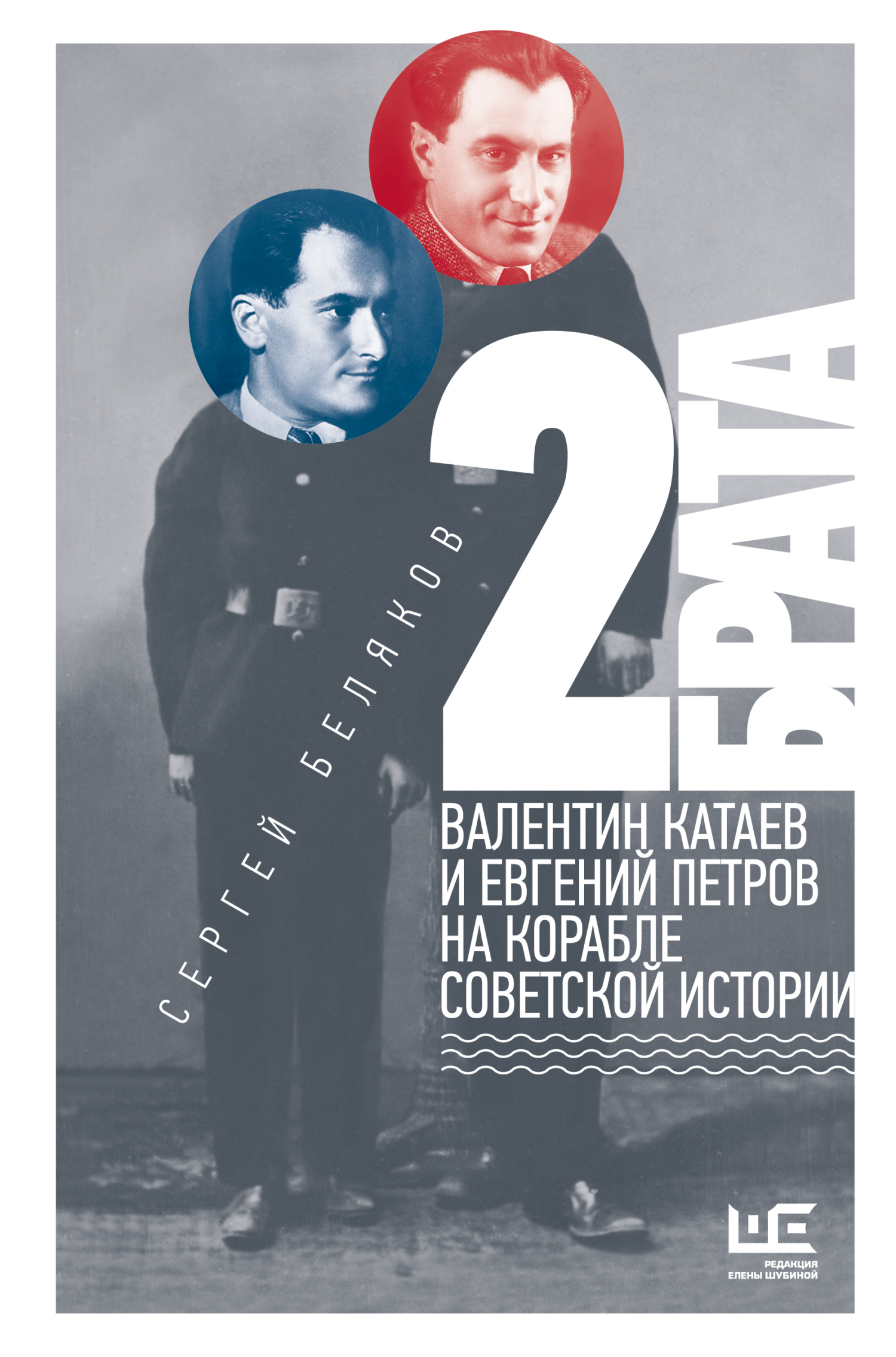

Sergey Belyakov

"2 brothers: Valentin Kataev and Evgeny Petrov on the ship of Soviet history"

Moscow : AST Publishing House : Edited by Elena Shubina, 2025. — 733 p.

There are more questions in "2 brothers" than answers that even the most thorough study of the archives cannot give, especially since not all documents that would directly or indirectly shed light on some twists of fate or the motives of Kataev and Petrov's decisions and actions have been declassified. The personality of his younger brother, Eugene, is particularly mysterious, partly because he was more secretive and restrained in his own diaries, notes and memoirs. Belyakov carefully mentions Petrov's mystery, for example, referring to the diaries of Vsevolod Ivanov: "The playwright Viktor Gusev once called Evgeny Petrov a mysterious man in a conversation with Vsevolod Ivanov. It definitely suits Petrov, especially in the last years of his life. In the distant past, there was a service in the Odessa criminal investigation department. For readers, he is primarily a satirical writer, journalist, author of feuilletons and essays that are published in Pravda, Litgazeta, Ogonka, and a member of the editorial board of the Crocodile magazine. But a little closer to the end of the book, in the sub-chapter "Who are you, comrade Petrov?" Belyakov gives Ivanov a full-length unfolding, for whom, it seems, all Peter's mystery was sewn with white threads: "V.Kataev is not so much an insensitive brute as a spoiled fool, corrupted by another very calculating brute, his brother."

This is the most evil, but at the same time almost the only openly negative statement in the book, the author of which copes well with the humane task of justifying and presenting in a more or less sympathetic light even such an odious figure as Kataev, whom many disliked both during his lifetime and after his death.. Nevertheless, Belyakov's greatest strength is not so much his own critical discourse or "lawyer's" eloquence in defense of his heroes as his work with documents. Tirelessly compiling the texts of the brothers themselves, their entourage, other witnesses of the described era (including such harsh and authoritative ones as Alexander Solzhenitsyn), as well as the findings and observations of other literary critics and historians, the author of the book arranges for the reader a truly fascinating "cruise" on the very stormy sea of Soviet history, which promises in the title and in which it was not easy for even a very talented writer to stay afloat.

The set of properties that were necessary for survival in the historical periods described by Belyakov appears in his book gradually, but quite clearly. One of the most frequently repeated quotes in the book belongs to Petrov: "In art, as in love, one cannot be careful," although it was precisely the caution of a tightrope walker swaying over a precipice that was required from a Soviet writer who walked a fine line between the inability to hide the originality of a personality, moreover, as self-confident as the Kataev brothers, and the need to play by the rules of literary nomenclature, to conform to the general line of the party, which tended to change quite unpredictably. Describing the virtuoso maneuvering that not only the heroes of the book, but also many of their colleagues, were engaged in in these extreme conditions, Belyakov himself also sometimes sneaks along a fine semantic line, trying to explain some moral and ethical nuances and gradations: thus, consistently calling Kataev a conformist and noting his cynicism, he nevertheless respectfully He notes that Valentin Petrovich still did not suffer from servility, and at least this reproach should not be hung on him.

Sometimes it looks funny that Kataev's "unsinkability", which was repeatedly threatened by serious danger, and not only on the fronts (where he managed to fight for both the whites and the reds), Belyakov explains throughout the book with a popular omen about the special luck of a man with two heads. In this, he draws on Kataev's own memoir, "A Broken Life, or the Magic Horn of Oberon," where the writer boasts, "It was believed that only rare lucky people have two heads," but Belyakov strokes these two Kataev heads at every opportunity. "Well, let's not forget that Kataev Sr. had two heads - a sign of a lucky, happy man," the author of the book once again emphasizes, talking about the late 1930s, when Kataev was almost reminded how, as a battery commander in the Red Army, he gave his soldiers the order to surrender.

To Belyakov's credit, it must be admitted that he uses not only superstitious arguments, but also more objective facts, in particular, the fact that both heroes of the book enjoyed the favor of one of the most terrible, in the author's opinion, people of the Stalinist era — Lev Mekhlis, the organizer of the repression in the Red Army, and later the editor of Pravda, where Ilf and Petrov worked very successfully and even made, in fact, on Stalin's instructions, an expensive and very fruitful trip overseas, which resulted in the book "One-story America." This embeddedness in the nomenclature, bordering almost on being caressed by the authorities, does not really fit in with the sense of freedom for which many generations of readers love the brilliant novels "The Twelve Chairs" and "The Golden Calf." Belyakov feels this cognitive dissonance perfectly ("How I would like to see my favorite authors of my favorite books ideologically close, like dissidents, oppositionists, freethinkers!"), including when describing the forced "ugly deeds" of both brothers, although it is difficult to say which of the Soviet writers did not commit such acts, trying to the last to evade, but still eventually signing the necessary collective letters or speaking at demonstration meetings and meetings (for example, in the trial of right-wing Trotskyists).

Belyakov tries to summarize the differences between Kataev and Petrov, as well as to finally rehabilitate them in the eyes of readers, and even before some kind of supreme court, in the sub-chapter "Black Swan, White Swan", where he polemicizes with the artist Boris Efimov, who wrote: "How unfairly and capriciously nature (or God) divided human beings between them." qualities. Why was the outstanding talent of the writer almost entirely given to Valentin Petrovich, while such valuable traits as genuine decency, correctness, and respect for people remained entirely with Evgeny?" Surprised by this famous phrase, Belyakov recalls the artistic merits of the books written by Petrov in collaboration with Ilf, and then embarks on more subtle arguments that in the case of Valentin Petrovich, one must still distinguish between correctness (which he did not abuse) and decency, which "in those days" required courage. An undoubted example of this, according to Belyakov, is Kataev's friendship with Osip Mandelstam, whom Kataev supported both morally and financially, and in general helped quite a few, albeit selectively, guided by his own internal criteria.: "... how can you not notice that Kataev fundamentally stands up for talented and brilliant people — for Stenich, Mandelstam, Zabolotsky. He stands up unsuccessfully, risking his reputation as a Soviet writer loyal to the Bolsheviks. A genius is worth risking for. But only a genius."

Переведено сервисом «Яндекс Переводчик»