- Статьи

- Culture

- Fight, Yefimov: why the exhibition of anti-fascist cartoons in Moscow should not be missed

Fight, Yefimov: why the exhibition of anti-fascist cartoons in Moscow should not be missed

A three-dimensional hologram of a sculpture, "revived" wartime memes, century-old newspapers and, of course, dozens of authentic drawings by one of the main satirical artists of the 20th century. The exhibition "Cartoons. Comics. Humor of the Fuhrer's personal enemy", prepared by Izvestia together with the Russian Academy of Arts, is timed to coincide with two anniversaries: the 80th anniversary of the start of the Nuremberg trials and the 125th anniversary of the birth of Boris Yefimov, the very master of the brush whom Hitler demanded to find and hang. And he survived not only his hater, but also the twentieth century. It was Yefimov's work that formed the basis of a large-scale project dedicated to the newspaper's anti-fascist activities. What the audience will see in the historical halls of the mansion on Prechistenka is in the Izvestia article.

Hologram and originals

Boris Yefimov is a remarkable figure for many reasons. He lived 108 years and got into the Guinness Book of Records as the oldest cartoonist in the world. He worked for Izvestia for 85 of these 108 years, creating a total of about 70,000 works. Shortly before his death, he was appointed to the honorary position of chief artist of the newspaper, having invented it specifically for Yefimov. However, this is just a beautiful formality, in fact, Efimov has been fulfilling this role since the 1920s.

Over many decades of hard work, a wide variety of politicians became the target of the "sniper of the Soviet caricature" (as Yefimov was called). But still, Hitler became the main object of ridicule. It was Yefimov's anti-fascist works that formed the basis of a major retrospective, which opens on November 19 at the Zurab Tsereteli Art Gallery on Prechistenka Street. And among the exhibits on display there are many surprises and such rarities that the public has never seen. The three halls cover three stages of Izvestia's struggle against the Nazi regime. In parallel, the fate of Yefimov himself is revealed.

As soon as we enter the exhibition space, we see a three-dimensional hologram with the artist's image. The basis of this work is the sculptural composition "Brothers" by Zurab Tsereteli. The famous sculptor sculpted the figure of Efimov back in 2004. And this is the rarest case when a lifetime monument was awarded not to a scientist, not an artist, not a statesman, but to a newspaper employee. Tsereteli portrayed Yefimov next to his brother, the publicist Mikhail Koltsov, who fell under the ice rink of Stalin's repressions. But the two-meter-high original, installed at the bottom of the gallery, cannot be moved to the second floor of the exhibition complex. And here modern technologies come to the rescue.

You can also see Yefimov together with Koltsov in the photos in the same hall — they are still quite children on the original card from the beginning of the 20th century. Contrary to the established exhibition practice, many of the photographs in this project are presented in authentic historical prints. Well, the biographical narrative is complemented by a documentary shown on a television screen and a timeline on the wall. By the way, there are two screens, and on the second one you can see how Yefimov draws, confidently tracing the lines of the caricature, which is born literally before the eyes of the viewer.

From drawing to newspaper

However, the main attraction here is not even the documentary materials, but the original drawings next to the newspapers of the 1930s, where they were reproduced. We can not only see the original, but also find out what place it occupied on the Izvestia page, what inscriptions and texts it was accompanied by... One of the tasks of the project as a whole is to invite the public into the backstage of newspaper life; to show which way the image invented by Efimov went from sketch to print. And this will be shown most vividly in the section dedicated to Nuremberg.

But we'll get to it later. Before that, the viewer will have to explore the second — central — exhibition hall dedicated to the Great Patriotic War. And it has its own drama. The left wall is dedicated to the image of Hitler by Yefimov. The right one is dedicated to the successes of Soviet soldiers in the fight against the Nazis. On the left is the dictator: small, funny, ridiculous. On the right is the people's hero. And Yefimov as a part of this nation. It is no coincidence that the topic of soldiers' letters arises in this context. Yefimov received regular letters from the front, thanking him for his drawings, which inspired faith in Victory and helped him not to be afraid of a formidable enemy, and asking him to send his works for reproduction in field editions. And they even asked for advice on how to learn how to create cartoons.

Yefimov treasured these plain, naive, and sometimes error-ridden messages all his life. Today we can see them at the exhibition, in the showcase. And immediately — listen to selected fragments performed by announcers and presenters of the Izvestia News Center: Like many other additional materials, audio recordings are available using QR codes that lead to a special project posted on the website. iz.ru .

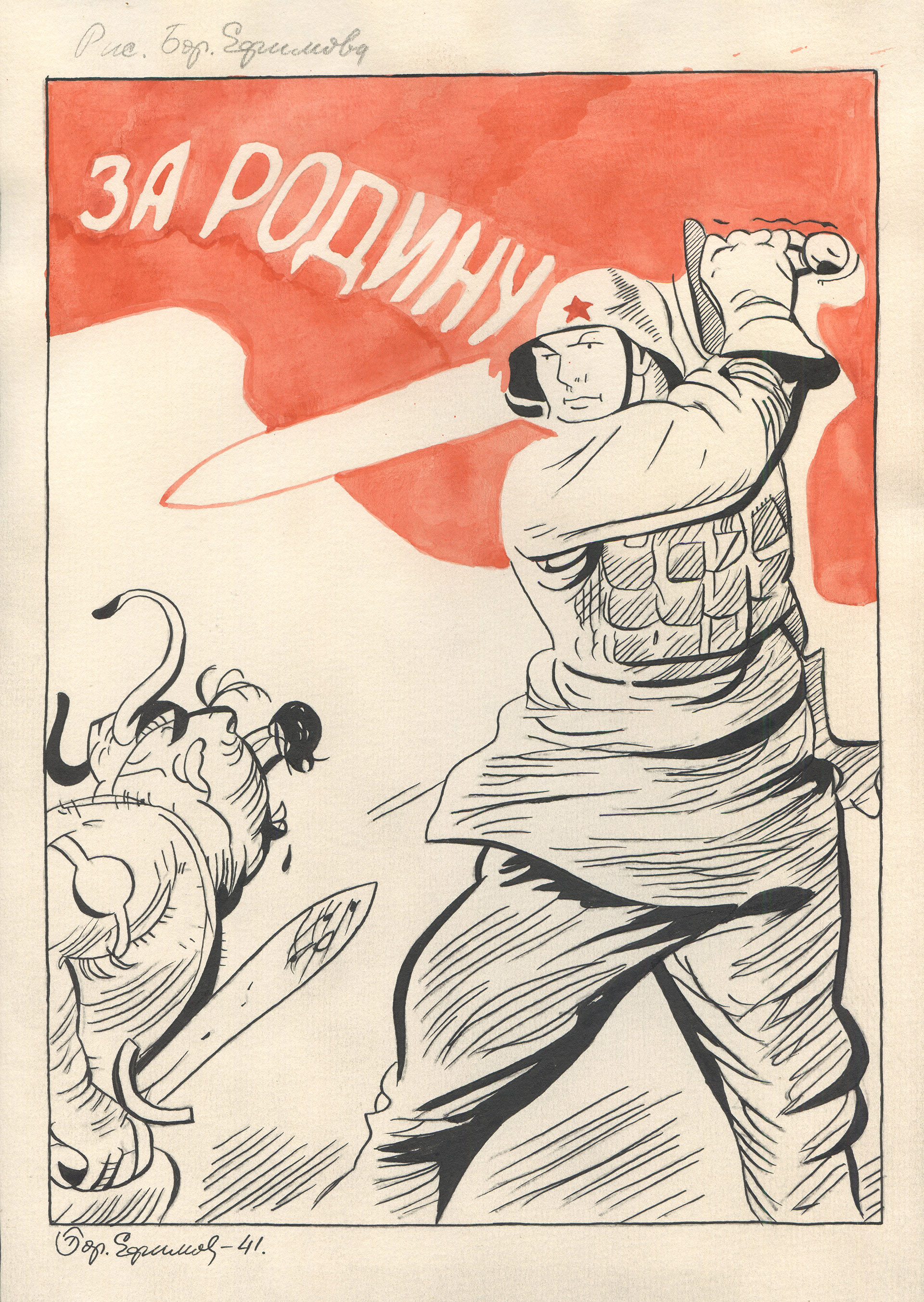

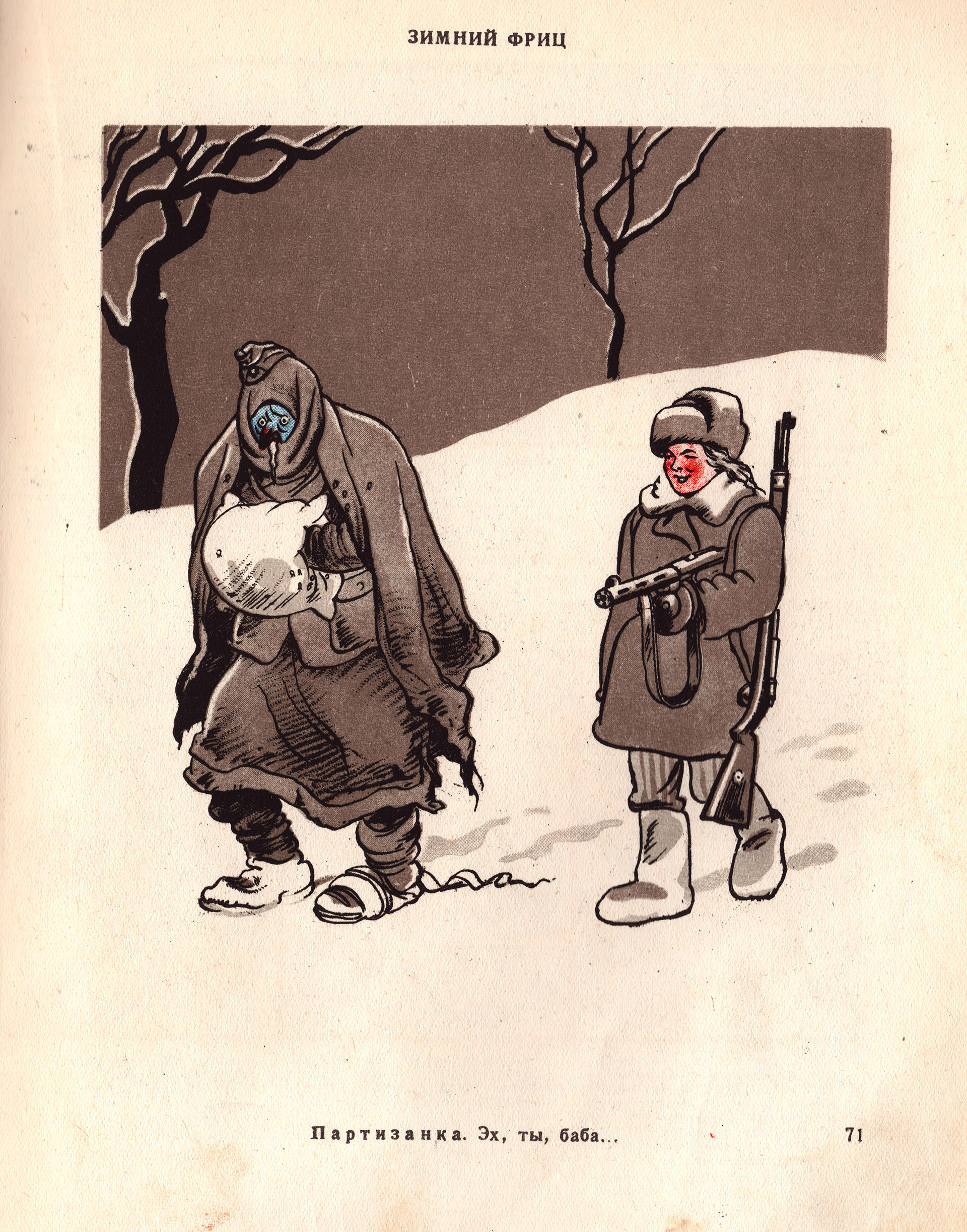

By the way, contrary to stereotypes, Yefimov painted not only enemies, but also Soviet fighters during the war years. And their image is no less expressive. For example, how subtly the artist shows a partisan girl who captured a German! The finished movie scene. But, of course, he doesn't laugh at ours. But by drawing Hitler and his pack, he gives free rein to schadenfreude and sharp humor 100%. That's exactly what Efimov's famous book, published in 1943 and sold in millions of copies in the USSR and many other countries, was called. And the main exhibit of the exhibition is connected with it: a large printing album, from which the collection itself was printed.

An album for Stalin

The story of this rarity is almost a detective story. Having collected his antifascist drawings from different years and manually pasted them on sheets of thick gray paper, arranging them in a certain sequence, Yefimov gave the album to the printing house. But when the book was ready and the artist requested the originals back, he found out that Stalin had requested some of the drawings to give to Churchill. The rest disappeared without a trace. Only this year, Izvestia's staff managed to discover a bulky folio in a private collection and buy it back for the publication's archive. Now everyone can see the find. The album itself is displayed in a showcase next to the book of the same name and a photograph of Stalin with Churchill. On the wall there are selected sheets from it and a TV screen with a slide show from the rest of the works.

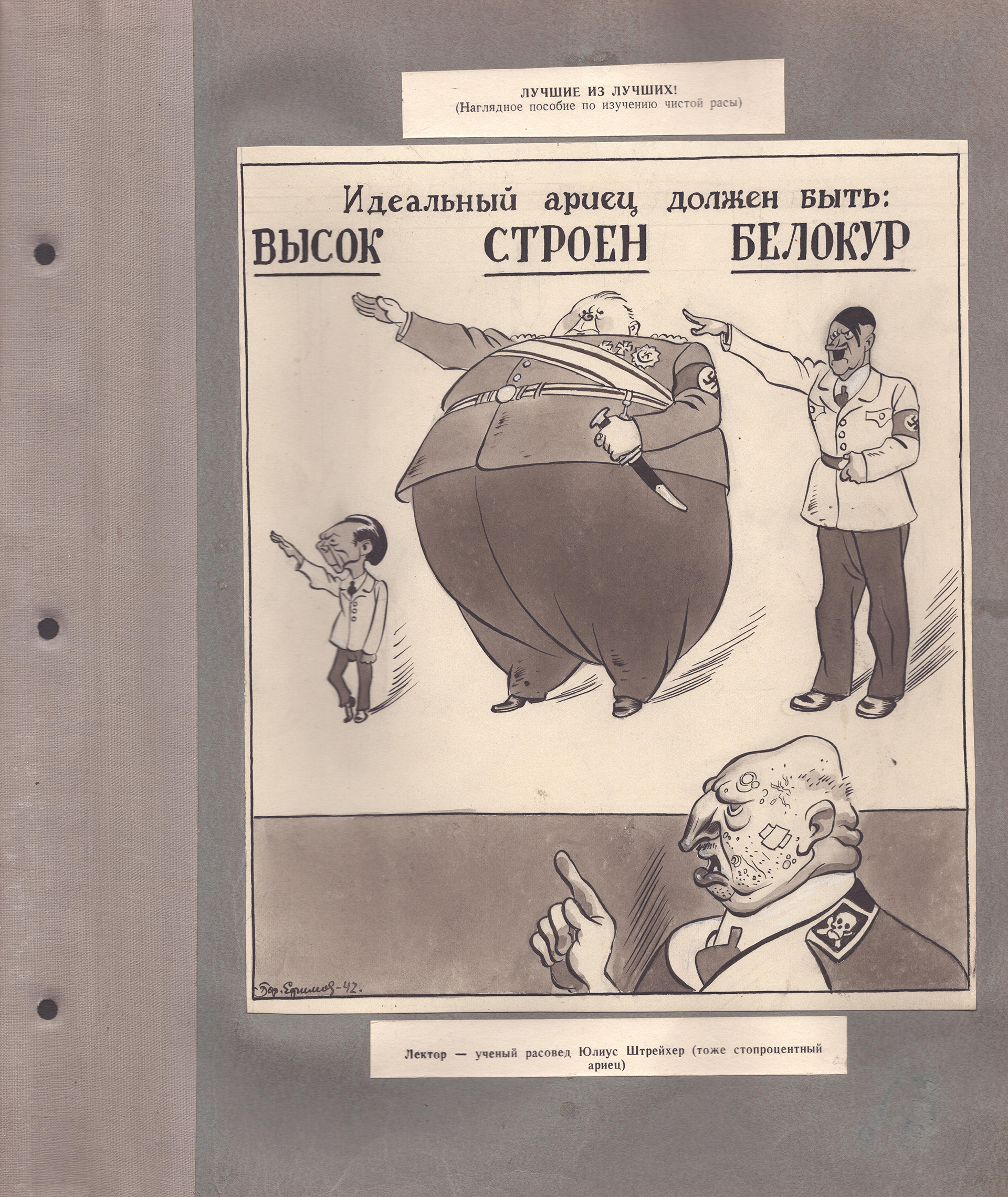

Landscape drawings are also used in other parts of the exhibition. And sometimes they form remarkable "duets" with works from the collection of the artist's family or propaganda posters from museum collections (they are also represented at the exhibition). Here, for example, are variations of the "Best of the best" motif. The name, of course, is mocking. Efimov shows what a "real Aryan" should be like: blond (portrayed by dark-haired Hitler), slender (fat Goering) and tall (short Goebbels). But in the sheet from the album, these three are dressed, and in the drawing from the home collection they are undressed. Has it been — has it become?

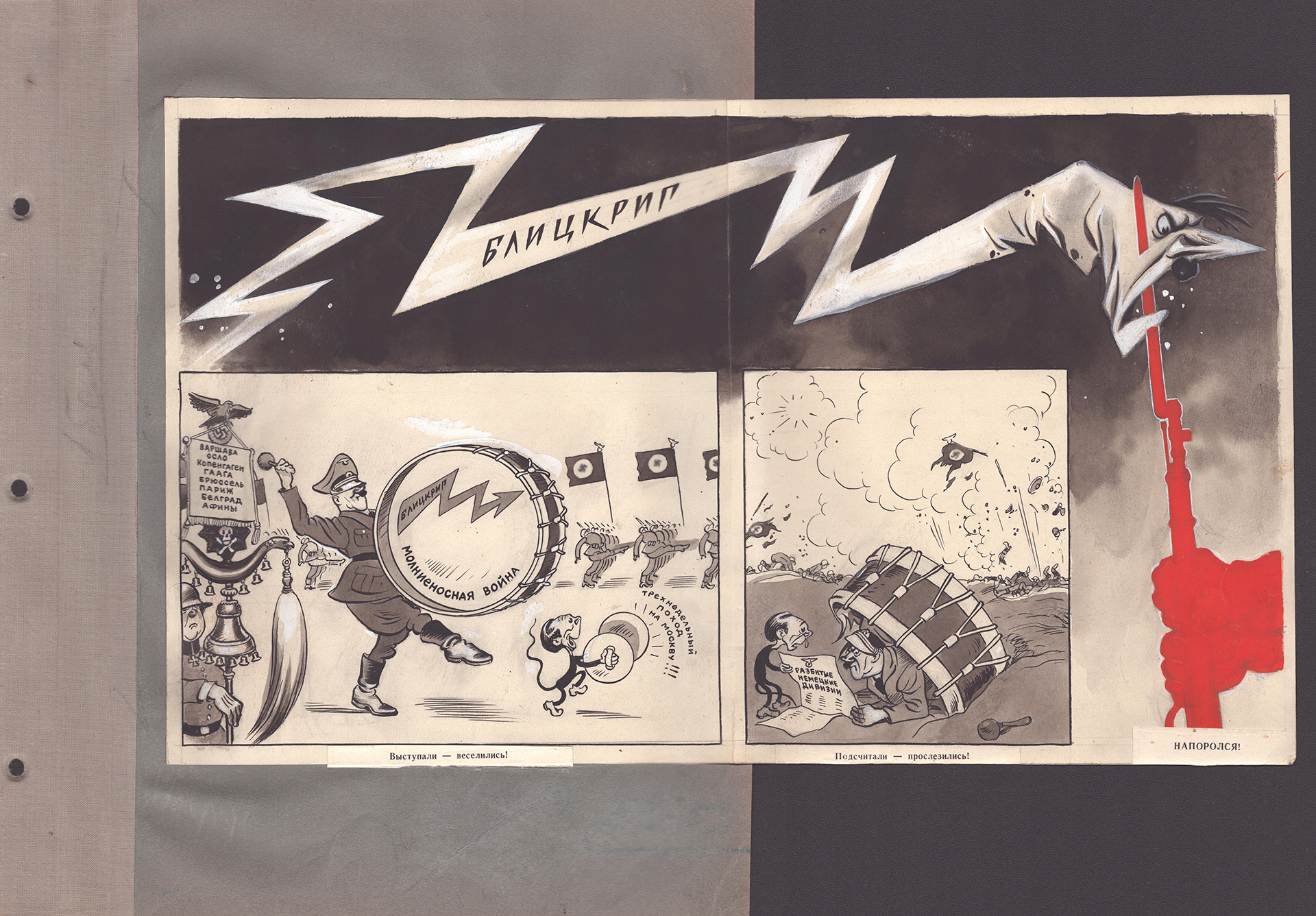

Or another pair.: "We performed and had fun." Here, Hitler and Goebbels are already depicted as circus musicians, joyfully marching and beating drums and cymbals. One can guess how the "performance" ended, but it is in the sheet from the album that the reason for the fiasco is most vividly and figuratively outlined. The snake-Hitler with the inscription "Blitzkrieg", which decorated the drum, is pierced with a red bayonet.

The red day of the calendar

Efimov, it should be noted, worked very concisely and accurately with color. Of course, this was not required for the newspaper, and therefore all his images are very graphic and expressive due to the form itself. But for flyers, posters, illustrations — quite. And the exhibition attempts to show the most striking examples of color inclusions, as well as to build a certain dynamic of "colorization" in the direction of its increase. It is no coincidence that the second hall ends with a drawing showing the front line on the map, and the entire eastern part is bright red.

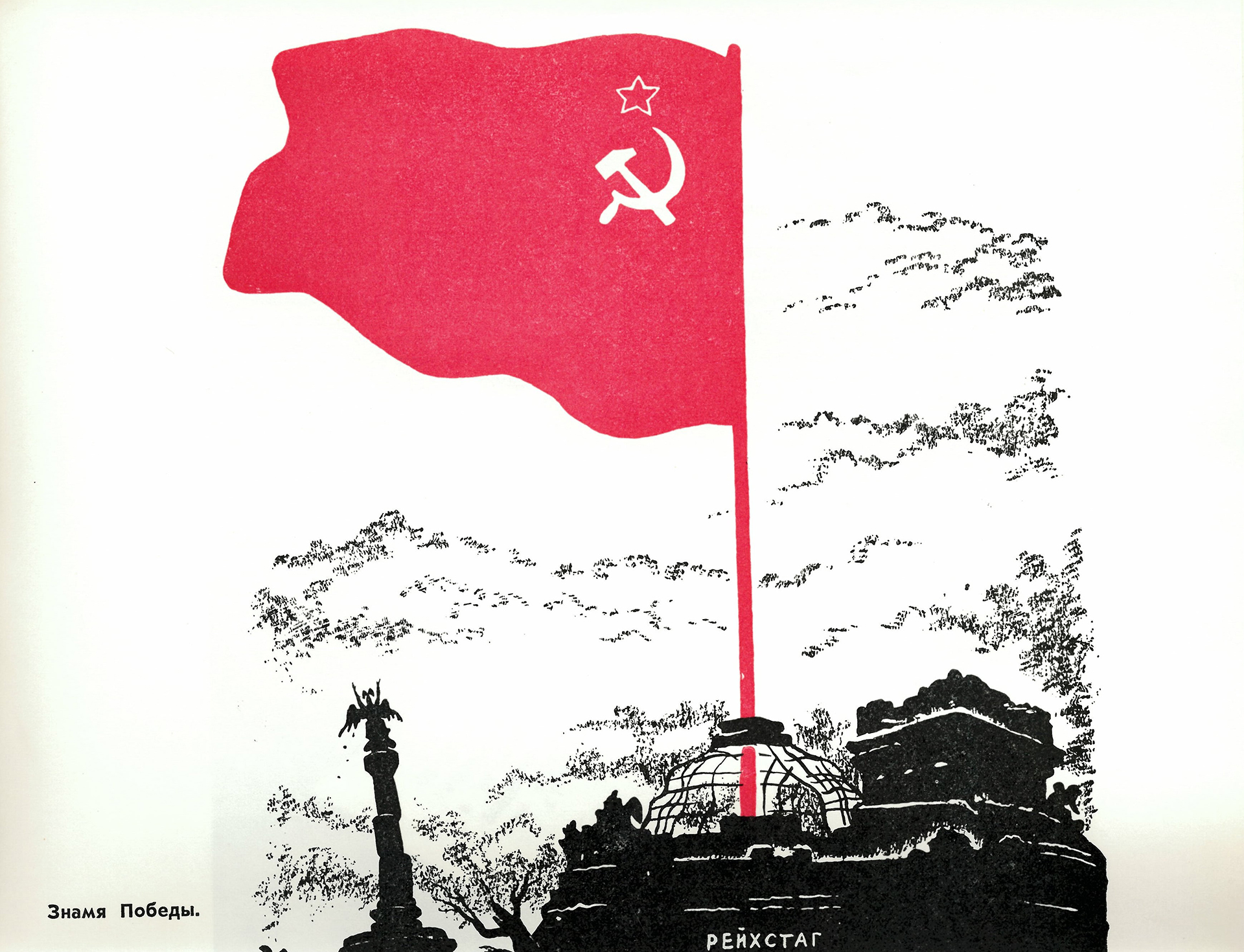

Well, the culmination of this line awaits us closer to the end of the journey. The visual dominant of the last, third hall is a huge screen with an animated drawing by Efimov depicting the Soviet banner over the Reichstag. But here's what's important: the waving flag is visible even from the very first room, since the TV screen is located exactly opposite the through corridor. The whole way through the exposition turns out to be directed towards the symbol of the Great Victory.

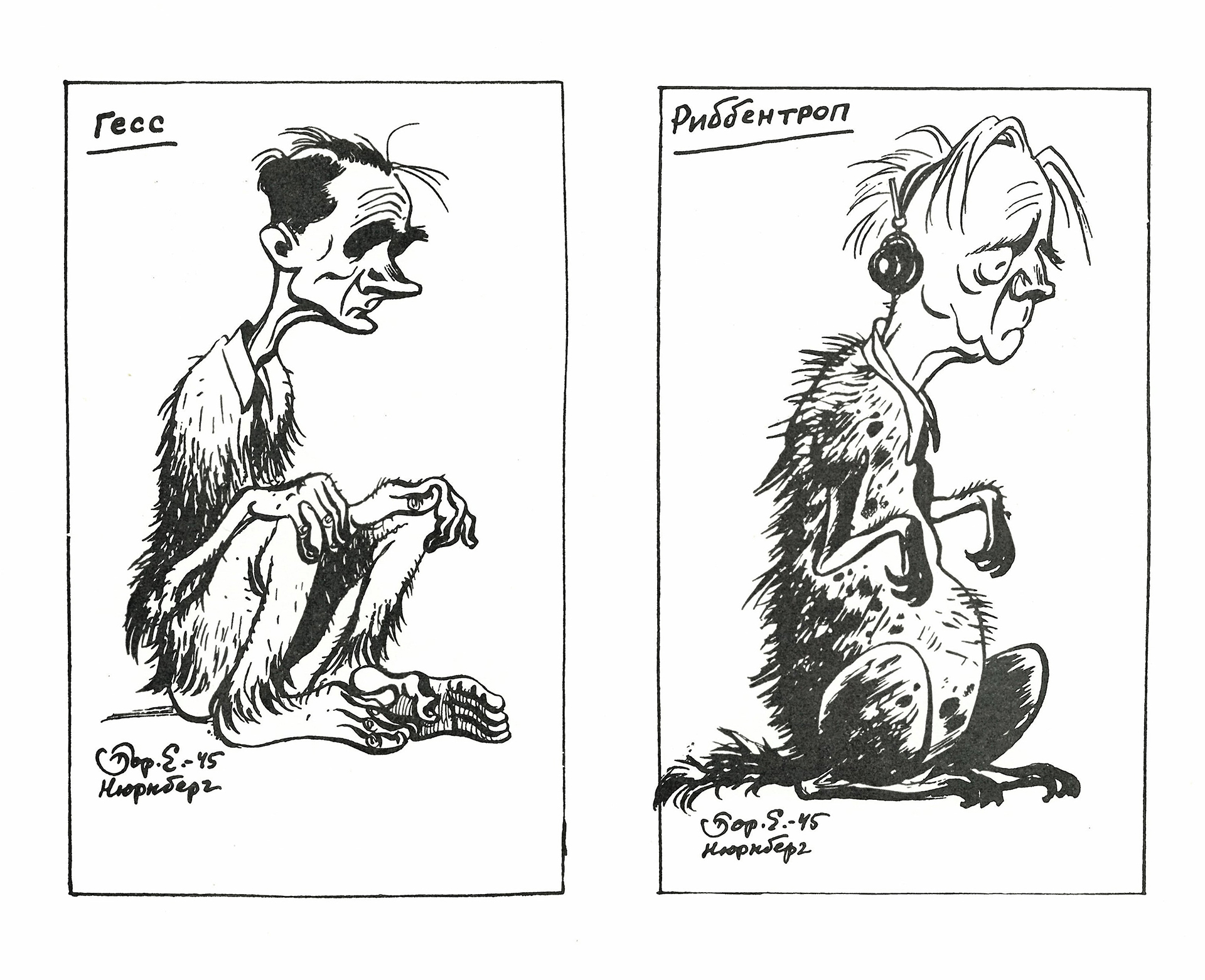

However, May 9, 1945, is not the end of the story. One of the key subjects of the exhibition is the Nuremberg trials, to which Yefimov was sent by Izvestia. And here the trick from the beginning of the exhibition is repeated: the archival issues of the newspaper are placed next to the original drawings. However, the originals are different. Portraying the defendants, Yefimov did not immediately find the key to the caricature. And we are clearly shown how this search took place. In the window is a sketchbook, the one in which the artist made pencil sketches right in the courtroom. They can be compared to ink drawings: the figures of Nazi criminals there are already more elaborated and caricatured. Finally, the final versions are on the pages of Izvestia: illustrations from the cycle "The Fascist Menagerie", where each of the leaders of the Third Reich is turned into some kind of animal or reptile.

Age and man

The final work in this series was published on January 1, 1946 (the newspaper was then published even during the height of the holidays). The defendants in the trial, sitting in the dock, turn to the clock, which strikes 12. There is a gallows loop around the dial. This is how the story of Yefimov's struggle against fascism ends. But the audience is still waiting for an important postscript. The artist paints the same bench a few years later, but the ghosts of the executed Germans invite Western politicians, recent allies of the USSR, who unleashed a geopolitical confrontation, to take their places. Churchill and the others recoil in horror, literally pressing themselves to the edge of the sheet. And now, in the next image, Eisenhower is leading tanks into the Arctic, aiming at a defenseless Eskimo. The Cold War began.

The exhibition clearly shows the continuity of Efimov's two themes. And, again, it reveals the inner newspaper kitchen: several later works on the topic of confrontation with the West are posted with editorial stickers indicating the data for the printing house and the note "Urgent to the room."

Boris Yefimov's whole life is a struggle: against fascism, against Western hypocritical politicians, and with life circumstances as such. Indeed, in Stalin's time, when his brother was called an enemy of the people, Yefimov's life hung in the balance. And trips to the front? And the Gestapo's dreams of capturing him? Each drawing could be the last one. But time after time he emerged victorious from the struggle with death. And the last of the exhibits presented is just about that.

Here is an auto garage where Yefimov draws himself over the number 100: yes, yes, this is a work from 2000, and it was created by a century-old artist. In the drawing, he runs — despite his age. And for whom? The viewer can answer this question himself. The curators of the exhibition offered their own version, placing the work next to the "Leaders", where all the Russian leaders of the XX century take place — from Nicholas II to Vladimir Putin (it's hard to believe, but Efimov saw them all live). He runs after history and with history.

A cartoonist, of course, is not a ruler. But, undoubtedly, he took his place in the history of Russia (and the world), as well as the characters of his friendly cartoon of 2002. His own path, albeit an exceptionally long one, has already ended. And the path of his works, their victorious, optimistic, ironic march, continues. The new exhibition confirms this.

Переведено сервисом «Яндекс Переводчик»