Russian "Spring"

Why did Igor Stravinsky's ballet Sacred Spring so shock Parisians? Why did the audience call the dentists during the performance? And is it true that Cocteau and Bakst rode on the roof of a car after the premiere, and the latter also waved an improvised flag from a handkerchief? The answers to these questions, as well as details about other masterpieces of the Russian Seasons, are in a new work by the famous critic and ballet scholar Rupert Christiansen. On the eve of the book's release, the Alpina non-Fiction publishing house Izvestia publishes one of the most fascinating fragments.

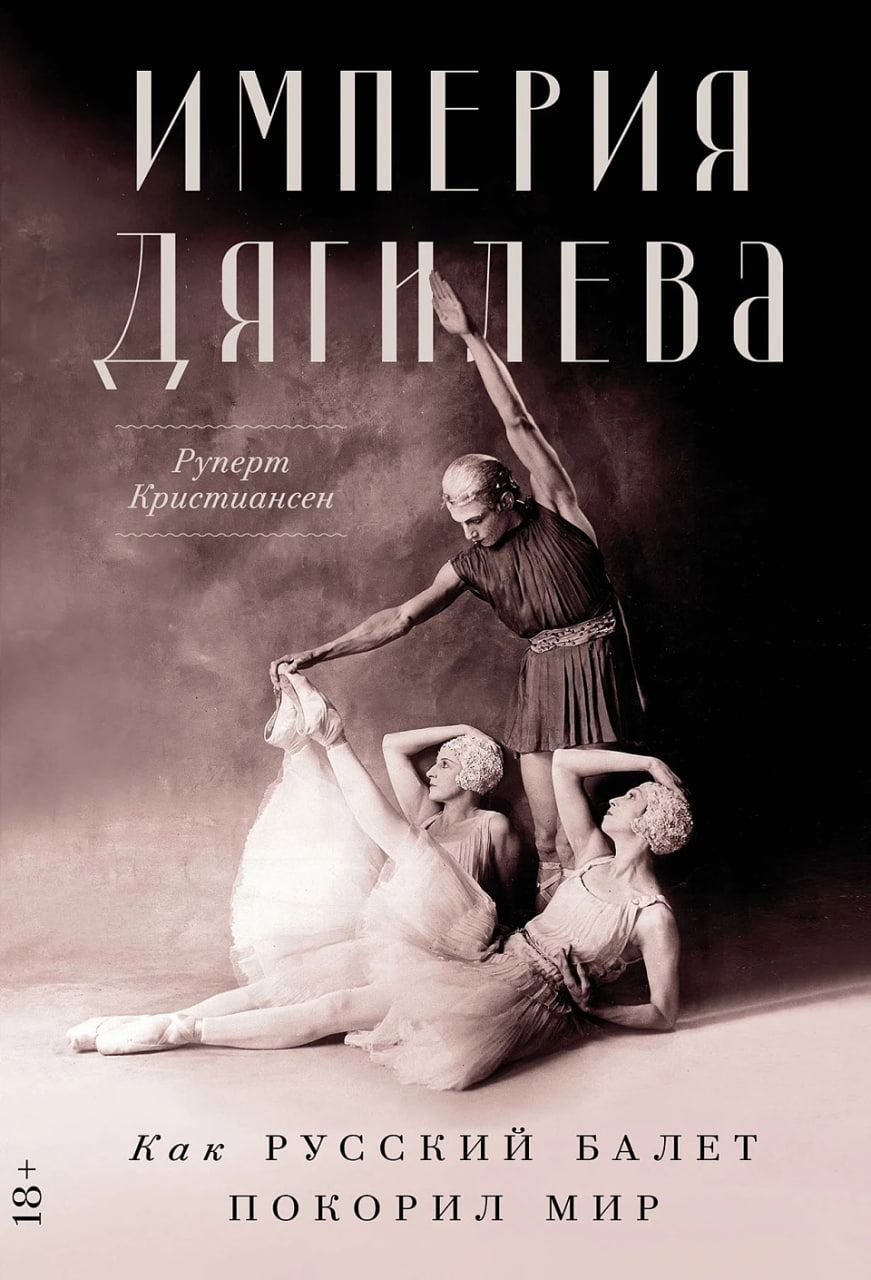

Rupert Christiansen "Diaghilev's Empire" (fragment)

"The Sacred Spring" (Les Sacre du Printemps) — the composer outlined it in one of the art centers of that time, the estate of Princess Tenisheva Talashkino, but composed mostly at the piano in his apartment overlooking Lake Geneva — turned into a thirty-five-minute ballet in two parts. It was a joint idea between Stravinsky and the polymath, mystic philosopher and amateur archaeologist Nicholas Roerich, who was passionate about ethnographic research and the study of the "barbaric" culture of the steppe Scythian tribes. His discoveries formed the basis of the libretto, where the action revolves around an imaginary pagan rite, when the patriarchal community meets the spring renewal of the fertile forces of the earth and sacrifices a young girl.

Initially, it was assumed that Fokin would be involved in the production of The Sacred Spring, but he left the Russian Ballet, slamming the door loudly, and Stravinsky disliked the choreographer, considering him "the most unpleasant of all with whom [he] had the opportunity to work." After some hesitation, Diaghilev assigned this enormous task to Nijinsky. In order to help him convey his ideas to the artists and pave the way through the unprecedented intricacies of the epoch-making score, Diaghilev hired a cheerful young teacher who studied rhythmics with Dalcroze. The teacher's name was Sivia Rambam: her native language, like Nijinsky's, was Polish. Over time, her name was smoothed out to Miriam Ramberg, and then to Marie Ramber: she played a prominent role in the history of British choreography.

From December 1912 to May 1913, including six weeks at the Aldwych Theatre in London, at least one hundred and thirty rehearsals took place, always very intense. Arranged for a large orchestra, the often highly dissonant, piercing music was characterized by a hitherto unheard-of rhythmic intensity. Played in the studio on a piano with all the syncopations, polyrhythmias and irregular dimensions, it was incomprehensible to the artists, and it did not help that Stravinsky himself came to accompany them, beating the rhythm with his fists and feet and shouting out the score as they performed, so fast that the dancers could not keep up with him. Ramber tried to maintain calm and order when the confused artists were desperate to adjust to the endless changes and alterations. Several inexperienced young English women had just joined the troupe: one of them was a seventeen-year-old Essex resident, Hilda Munnings, whose unpleasant name was unconvincingly Russified in the list of performers as Maningsova; later she would invent a more flattering pseudonym Lydia Sokolova, taking the surname of a famous Russian ballerina of the 1880s. Her memoirs are one of the most reliable accounts of the Russian Ballet; she described how during rehearsals, ballerinas "ran around clutching pieces of paper and arguing in a panic about whose score was correct and whose was wrong."

Nijinsky's insistence on strict compliance with all his instructions further complicated matters: despite his short temper, Fokin always allowed some freedom of opinion and interpretation, while Nijinsky was inflexible in the army and did not know how to explain his commands to the troops. The rehearsals turned out to be a monstrous ordeal for the troupe. To match the scenery with "gloomy, semi-wild, semi-mystical landscapes," as Beaumont describes them, Roerich created native peasant costumes in which there was not a hint of ballet elegance and practicality: long thick wigs, false beards and dresses made of coarse homespun linen with mysterious symbols embroidered on them not only had a repulsive appearance — It was uncomfortable and hot to dance in them. Ramber described Nijinsky's concept as follows: "The feet are turned inwards, the knees are bent, the hands are in the reverse position of the classical, primitive, prehistoric pose. The movements are very simple: steady gait or stomping, jumping mostly with both feet with a heavy landing." Artists with their heads tilted to one side and their faces heavily made up were asked to get rid of their previous ideas about academic training, hierarchy, and gender differences in favor of something plotless and untenable that required them to be extremely focused and fearless.

As in the case of Fawn, Diaghilev foresaw and to some extent ignited the scandal himself, provocatively announcing in the press "a truly new sensation that will undoubtedly cause heated discussions." And so it happened: they say there are at least a hundred testimonies of the furore that, as expected, produced the premiere of the play in May 1913. They are extremely different, and sometimes directly contradict each other. I must say, some of them hardly mention the uproar: after all, whistling and booing were the usual reaction of the Parisian public to innovative productions: shortly before that, the Afternoon Rest of the Fawn received a harsh reception, falling victim to this shameful tradition, the usual occupation of drunken young idlers who booed the premiere of the drama "Ernani" in 1830."Victor Hugo (too close to the ideology of the left, too freedom—loving), in 1861 — Wagner's opera Tannhauser (there are not enough ballerinas in the second act), and in 1891 - Ibsen's drama The Wild Duck (she was greeted with friendly quacking).

Modernist trends have become an obvious target for both pretentious zealots and cynical bullies. Jean Cocteau described the audience of the Champs-Elysees Theater as a toxic collection of "thousands of variations of snobbery, oversnobism and antisnobism," and it apparently belonged to the same social class as the guests of Madame Verduren's salon ridiculed by Proust or visitors to the earlier exhibition of Italian futurists who had gathered for its opening in "elegant cars, limousines and convertibles <...> to giggle and sneer." Harry Kessler was among those who recorded their impressions immediately after the premiere of The Sacred Spring, leaving in his diary one of the most impartial accounts of the audience's behavior: "The audience, the most elegant I have ever seen in Paris <...> from the very beginning could not calm down, laughing, whistling and joking". When supporters of different factions began exchanging streams of witticisms and abuse, "the excitement became universal... above the frenzied roar, there were bursts of laughter and contemptuous clapping, while the music boomed furiously and the artists, without batting an eye, circled in a primitive dance."

Other witnesses claim that the police had to be called because of the fights, but there is no reliable evidence for this, and one can only assume that for the most part something beyond reason was going on in the hall-as Cocteau cynically said, "the audience behaved as they should have." However, there was no question of any failure. "At the end," Kessler wrote, "the Beau monde and demimond burst into a stormy, incessant ovation, forcing Stravinsky and Nijinsky to bow several times."

That evening, amid a riot of ridicule, some of the audience were nevertheless deeply moved by the production. Those who watched and listened without prejudice felt her burning nerve. The American writer Carl van Vechten described this event as follows::

"There was a young man sitting in the box behind me, and during the ballet he stood up to get a better view of the stage. The intense excitement that gripped him was expressed in the fact that he began to beat the rhythm, tapping the top of my head with his fists. I was so excited that I didn't immediately feel the blows."

It wasn't all fake. "We were both overwhelmed with feelings," van Vechten concludes his story.

On the other side of the ramp, there was an alarming tension: the unfortunate dancers were trying not to get lost and lose count. Their faces expressed such despair that the wits from the gallery began calling for doctors and dentists. Lydia Sokolova recalled:

"The screaming and whistling in the hall started almost simultaneously with the music, and by the time the curtain was lifted, we were pretty scared. Grigoriev wrote in his book <...> that "the actors <...> were calm, some were even amused by such an unprecedented incident at our performances." I can only say that I personally wasn't amused at all."

According to Stravinsky, conductor Pierre Monteux stood in the orchestra pit "outwardly unperturbed and calm as a crocodile"; Nijinsky, from behind the scenes, shouted out a complex rhythm in the midst of all this hubbub (but in vain: as Stravinsky explained, "in the Russian language, all numerals over ten are polysyllabic <...> and with such a fast pace of movement, neither he [Nijinsky] nor they [the artists] could keep up with the music"). It's unclear how they managed to perform the ballet in full, but when it was over, Nijinsky took to the stage to calm the disheveled audience with a gentle fantasy of "Visions of the Rose."

"This is exactly what I was waiting for," Diaghilev said carelessly about the commotion, going to a restaurant with close friends. Kessler wrote that later, together with Diaghilev, Nijinsky, Bakst and Cocteau, they "took a taxi and set off on a crazy ride through the completely deserted, moonlit streets of Paris — Bakst tied a handkerchief to a cane and waved it like a flag, [they] with Cocteau climbed onto the roof of the car, and Nijinsky in a tailcoat and Top hat was smiling contentedly to himself."

Cocteau has slightly different memories: they drove in silence to the Bois de Boulogne, where Diaghilev suddenly began to recite something from Pushkin by heart and began to cry, overcome by nostalgia for Mother Russia.

Переведено сервисом «Яндекс Переводчик»