Irina the Great: how the director of the State Museum of Fine Arts ruled his empire

One of Irina Antonova's favorite and most ambitious projects as president of the Pushkin Museum was the exhibition "Voices of Andre Malraux's Imaginary Museum." Based on the title of this symbolic exhibition, the famous writer, literary critic, and winner of the Big Book Award Lev Danilkin titled his new book "Madama's Palazzo: The Imaginary Museum of Irina Antonova." This is an extensive and in many ways unexpected biography of Irina Alexandrovna. On the eve of the premiere, Izvestia publishes an exclusive fragment of the book.

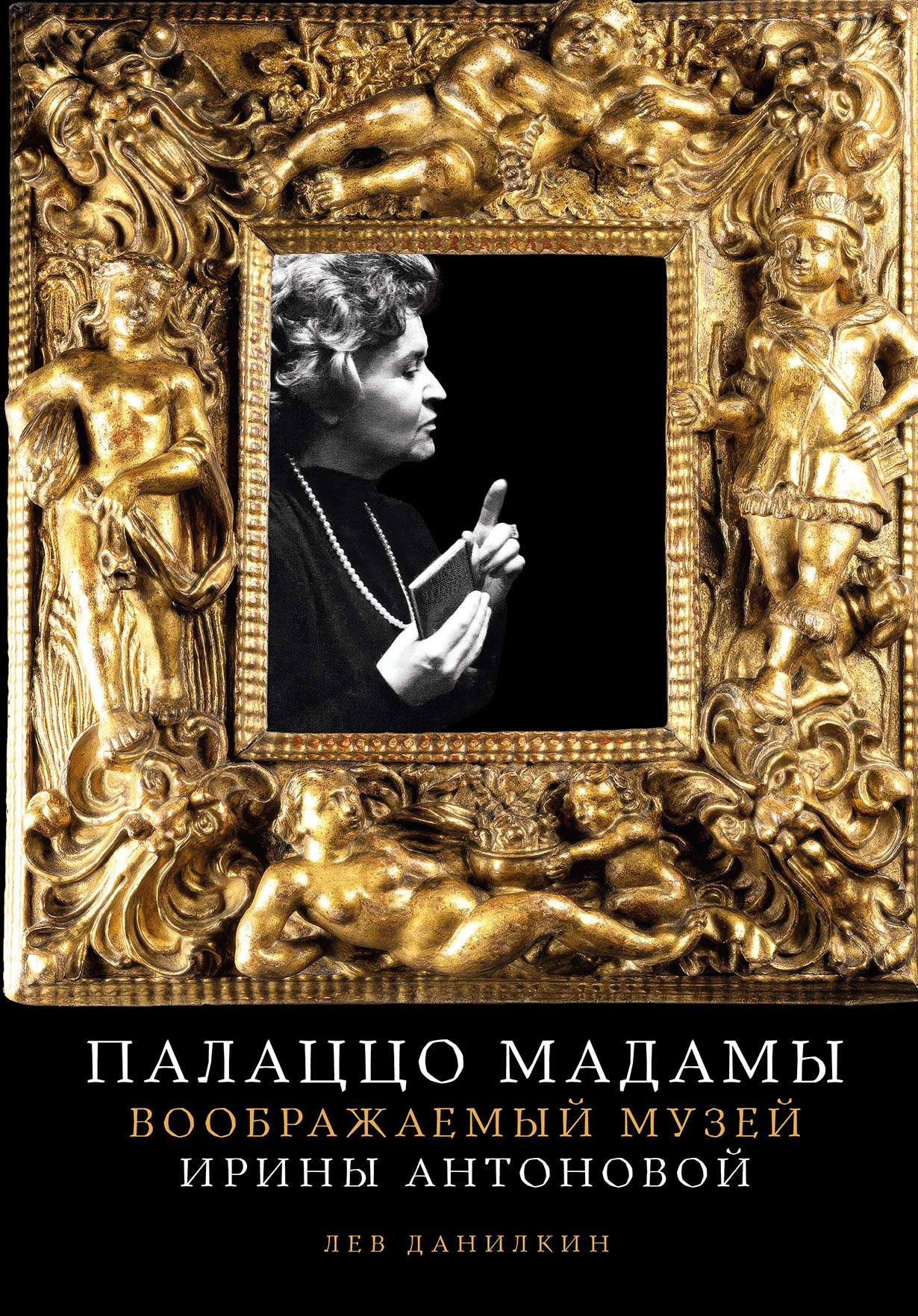

Lev Danilkin "Madama's Palazzo: Irina Antonova's Imaginary Museum"

The official history is always histoire événementielle: a chronicle that is written based on a dotted line of Major Events; if Pushkin, then here is the first Picasso exhibition, here is La Gioconda, here is Moscow – Paris, here is the first Beuys show. However, even if this is the biography of a Museum director whose career depends on the number and quality of major events, there is also a microhistory: everyday interactions of people in the same public space, and not necessarily related to the state, eternity, or ideologies.

It's strange that no one seems to have made a series in the manner of "Mozart in the Jungle" about an ambitious and hyper-responsible director of a small museum.: how he gets objects for exhibitions from colleagues, churches, and individuals, by hook or by crook; how he composes obviously unpromising ones — without the right to fail! — suggestions "for currency-free exchange of artistic works"; as grabs his head, knowing that the film — which is already a few years ago the roof was leaking — ripped hole movers; as accountable to the beholder of the bodies, why are your employees bring to the Museum of foreigners; how to break two widows of one artist who started the fight for the inheritance of paintings directly in the Director's office; as arguing with the Ministry, Ambassador, attaché, requiring the issue of a painting that issue for some reason do not want or can not, and in case of rejection he faces the fact that the Museum never anything of this country will no longer receive; as escapes in the middle of the concert with their own "December nights" after the call of the Minister, plazewski in English and Dutch press that the auction allegedly exposed a few pieces of graphics from the disputed collection Koenigs, to urgently open the vaults and see a folder with the stored leaves didn't steal it, that's all; like yelling at the fools who, knowing that you have agreed with the printing on the print catalog, today is the final deadline and if you do not take the texts, the exhibition will open without a catalog, wrote nothing (or worse, written, and there is sedition, which the exhibition is immediately closed, and the remake once); as their rescues of renoirs, van goghs and Goganov, which was lucky for exhibition at the Swiss Martigny — and suddenly, in the amount of 55 pieces, the insurance cost more than $1 billion, was arrested right in vans, on request, with claims to the Russian company.

It's not surprising, when you have a warehouse of art treasures, a secret storeroom for military trophies, a platform for diplomatic rituals, a nest of dissidents, and a children's studio, that something wrong happens here all the time in addition to the planned events. Preserved and accessible explanatory notes to the Ministry of Culture, as well as the minutes of the directorate, describe a whole bouquet of incidents: "On January 20, 1960, in one of the exhibition halls of the Pushkin State Museum of Fine Arts, during the repair of electric lighting, a glass ceiling fell over the glass ceiling, fragments of which damaged one of the exhibits and only by a happy coincidence did not touch any of the visitors (in particular at that time there were four children's excursion groups in the hall)". "Yesterday, August 8, at 17:3 p.m. in the hall of the Greek exhibition "Acropolis 1975-1983. Study, research, restoration work"the stand under the marble sculpture "The lower part of the sixth caryatid of the Erechtheion" (inv. No. 7163) collapsed spontaneously, as a result of which the monument fell to the marble floor and several fragments of genuine marble and part of the plaster cast broke off." "On October 7, 1985, at 2 p.m., while walking along the colonnade where the exhibition of paintings of the Mloda Polska association is located, a visitor to the exhibition, L.S. Gazarov, tripped over the podium, fell, and during the fall he caught a folded closed umbrella and tore through V. Hoffman's painting "Concept".

Correspondence management is a very significant part of the director's routine activities. You have been corresponding for months with related organizations about ordering a carpet for the Pink Staircase and uniforms for employees for the Olympics (the department of manuscripts has a whole folder of documentation on this subject); with competent authorities about the intrusion of an intruder into the museum building at night and increased security; with seventh-grade girls who have become victims of Stendhal syndrome when visiting an exhibition — and sending money to the director asking him to buy a bouquet of flowers to put in front of a painting by Mantegna ("Dear Natasha, I was very touched by your letter. It's good that you understand art so accurately and correctly. And not only art, but also the more general tasks that the Museum sets by organizing exhibitions. I am sending you the catalog and wish you and your loved ones good health and happiness. We put the flowers, as you requested, on the box with the painting by Mantegna. Sincerely, IA"); with its own personnel department — personally approving employee internships, adjusting bonuses and writing specifications for personal files; with Aeroflot — which treats the transportation of works of art carelessly, constantly damages museum cargo and at the same time refuses to let escorts onto the airfield; with inventors and innovators — who came up with the latest device for cleaning the soles of shoes and reasonably came to the conclusion that the State Museum of Fine Arts is the ideal place to introduce it; with madmen, squabblers and just the owners of a lot of extra time.

A special article is devoted to responding to complaints and writing them; it is difficult for outsiders to imagine to what extent the museum is a bottomless storehouse of material for denunciations. So IA responds to his superiors at the Ministry of Culture to eight letters and postcards received by the Museum from US citizen Philip P. Thompson, who "was very surprised that the paintings of only one American artist Rockwell Kent are on display in the museum ..." (IA verdict: "The tone of the letters gives reason to believe that their author is a mentally unstable person"). The news agency itself complains (in the 1980s) to Deputy Minister of Culture P.I. Shabanov about the Moscow City Cloakroom Service Plant — strangely, the museum cloakroom staff worked in another organization and did not care about the specifics of the institution: "... they undermine the authority of the museum. They come to work drunk, swear, and treat visitors incorrectly, including many foreign guests." What should I do? "We need 28 full—time cloakroom staff - our own." And then there's the economic background of the case: "The average rate of hooks per cloakroom attendant is 110 pieces. The number of rooms in the Museum's cloakroom is 1,500. Monthly salary is 70 rubles."

Any large museum would be an excellent material for Dutch genre paintings like Stenovsky or Teniers, illustrating what happens when "the mistress of the house fell asleep and everything went wrong"; Pushkin — if not "especially", then certainly "not an exception". Despite the fact that in the mind of the layman, the Museum is a smoothly functioning machine, all the cogs of which must comply with the regulations. In fact, first of all, "people of art" ignore the rules due to absent-mindedness or general disorganization, and technical workers — because the state underpays them; secondly, both of them are often not doing what they should be doing - and, sometimes, instead of filling out catalog cards, They flirt, celebrate holidays, and go shopping; thirdly, there come moments when chaos reigns instead of perfect order.

The reference day in this regard was March 9, 1965, when it turned out that Frans Hals' painting "Evangelist Luke" had been stolen from the State Museum of Fine Arts (estimated value in official documents is 110-120 thousand rubles). Later, an unpleasant wording would appear in the documents — "the negligent attitude of the employees" who, during a routine inspection, inspected hall No. 7, but missed that instead of the painting there was only one frame with a cut—out canvas, and it was discovered only the next day. The thing is that there was a sanitary day at the Museum and the staff celebrated March 8 by inertia.

According to I. However, it was not possible to hush up the scandal: "... they did not ring all the bells, but it leaked anyway, and the BBC reported."

IA recalled the story with Hals infrequently and reluctantly, perhaps also because she herself was not in Moscow at the time of the theft, and judging by the fact that 19 days after the incident, the director's office was still empty, she was somewhere far enough away; if you check the known calendar of her trips — in Japan, where they showed "Masterpieces of modern Painting from the USSR," the State Museum of Fine Arts, that is, the Hermitage.

The investigation lasted for many months, and it hardly favored the continuation of IA's directorial activities: detractors did not have to make special efforts to present the incident as a failure of the head. It was especially painful for IA and her colleagues that one of their own had committed the crime: there were no outsiders in the Museum, so they mostly dragged employees for interrogations.

Fortunately, they managed to catch the kidnapper in the fall — he turned out to be really officially listed as a restorer of the State Museum of Fine Arts since 1963. The wolves.

On February 23, 1966 (after the trial), IA held a general staff meeting, reconstructed, as a prelude and in the manner of Poirot, the full picture of the crime - after which she gave a lengthy lecture on vigilance and labor discipline, especially about the procedure for hiring new employees: from now on, only with iron recommendations.

The list of victims included the abductor of Wolves himself (who lost the opportunity to continue restoration activities at the Pushkin Museum due to the sentence of 10 years in prison that came into force), the hall attendant (who was removed from work) and convicted of knitting at the post while there were no visitors, the museum caretaker with the speaking surname Storozhenko (transferred to cleaning, plus a severe reprimand with a penalty).

The successful ending of the detective story, which looked like the blue dream of Petrovka 38 (criminality in the temple of art, attempts to sell a masterpiece to a foreigner, a double—bottom restorer, a sealed crime detective in a locked room), led higher profile organizations to the idea of using this plot as an advertisement for law enforcement agencies: a good state is not where there is no theft and where criminals are found and punished. Immediately after the trial, inquiries were sent to the Museum, supported by the Ministry of Culture and the Ministry of Internal Affairs, about the possibility of shooting a feature film about the theft in the museum decorations.

The last thing an IA would like is to be associated with a scandalous story that has already been dragged apart by the press. But no matter how much the State Museum of Fine Arts wanted to quickly remove this stain from its snow-white reputation, no matter how much it demanded to remove from the script all the details that could make it clear that it was about Pushkin, the cinematographers had to open the door, and the consultants from Petrovka had to smile wider. "The return of St. Luke was shown on big screens already in 1970; the dynamic plot - as well as the actors Sanaev, Dvorzhetsky and Basilashvili — provided the film with a decent audience; fortunately, the Museum director was not among the characters.

The incident, which half a century later is perceived as an anecdotal incident, in 1965 became a severe ordeal for all employees.

Moreover, the cloakroom staff's commitment to drunkenness and bad manners, as is often the case, went hand in hand with an inability to concentrate on performing their direct duties — a sad fact confirmed by the story of one employee who unwittingly witnessed a conversation between the director and a visitor who burst into her office, indignant at the loss of a deposited hat. In response to the angry man's curses, EEYORE simply asked: "How much does your hat cost?" and, without haggling or blaming the cloakroom staff, she took a purse out of her bag and handed the victim the amount he named.

The painting did not belong to the State Museum of Fine Arts, but to the Odessa Museum, where two paintings from the cycle are kept at once, it was brought to the exhibition of European paintings from the collections of museums of the USSR. They have long been considered the work of an anonymous Russian artist (in fact, this is not a "typical Hals" — the artist's only experience in religious painting; no "Renaissance elbows" and good—natured smiles; all four are pure Platon Karataevs), but art historian Linnik, despite the lack of signatures and direct analogies in Hals' work, proved that what is Hals: the Evangelists Luke and Matthew.

Переведено сервисом «Яндекс Переводчик»