At the crossroads of temporalities: The metamorphoses of Russian shoe discourse

The book by an employee of the State Museum of the History of St. Petersburg is devoted to women's shoes of the XIX-XX centuries, the history of the appearance of various models and their influence on culture. Details can be found in the Izvestia article.

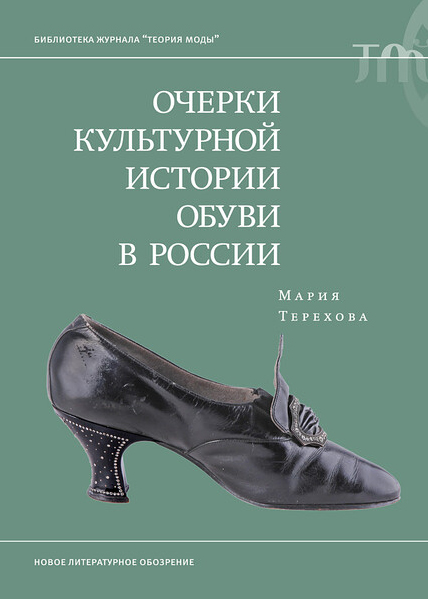

Maria Terekhova

"Essays on the cultural history of footwear in Russia"

Moscow: UFO, 2025 — 324 p.

The book by Maria Terekhova, an employee of the State Museum of the History of St. Petersburg, grew naturally and organically from the catalog "Women's shoes of the XIX-XX centuries in the collection of the State Museum of Fine Arts of St. Petersburg" – the first complete scientific description of the museum's shoe collection in Russia, compiled in 2022. Describing and systematizing museum boots and shoes, categorizing them, the researcher at the same time tried to comprehend each item culturally and historically.

Stating that the experience of such understanding has no significant analogues in Russian cultural studies (applied publications on shoe design and technology "do not actually address the issue of cultural semantics of shoes and suits"), Terekhova does not pretend to be "inclusive" of her research, hence the modest genre definition — "essays". However, the collection of these essays is not limited to scattered observations, but, on the contrary, makes a very complete impression thanks to cultural and semiotic optics, which serves as a methodological basis. "The cultural meanings of material things are a complex, complex subject of research. Therefore, in the search for keys to interpreting shoes as a cultural text, one has to turn to concepts from the field of sociology, cultural anthropology, art studies, and methods of discourse analysis," the author writes.

However, the most valuable thing in the resulting "Essays ..." is not so much the impressive categorical apparatus and sonorous terminology with references to such authorities as the French interpreter of everything Roland Barthes or the classic sociologist Georg Simmel, but the emotional component. It is especially noticeable in the finale, when the author is no longer just theorizing, but picks up someone's shoes and tries to imagine the one who wore them, even though she has been dead for a long time.

But in order to leave such a literal trace of his stay in the world to posterity, a Russian citizen had to make remarkable efforts from time immemorial — this is one of the cross-cutting thoughts of Terekhova's book, which explains in detail why it has always been difficult to put on proper shoes in our country. It's not just about the catastrophic "shoe famine" of the First World War and the Civil War, when the shoe industry shifted to military needs. It is not for nothing that one of the chapters devoted to the era of Stalin's "Great Turning Point" has the subtitle "Nothing to put on shoes again."

But also about the fact that in the first decades of the 19th century, from which Terekhova begins her historical excursion, "only a small part of the townspeople could afford to put on shoes in first-class shops among mirrors," and the general public was more content with the services of artisanal shoemakers, among whom there was a hierarchy. "High-class shoe artisans were called "tops" — they "perfected their skills to art," Mikhail Prishvin's 1925 essay "Shoes: A Study of a Journalist" quotes Terekhov. "The opposite of gyroscopes were the so—called teamsters—those who cared primarily about quantity, not quality."

Analyzing the features of pre-revolutionary shoe production, in which progressive mechanization and traditional handicrafts coexisted, the author identifies a problem that is not so much economic as anatomical in nature: shoes were not always suitable for the buyer. "St. Petersburg local historian Peter Stolpiansky believed that a manufacturer could only make shoes for a normal foot, and it is very rare," the author writes. According to Terekhova, Stolpiansky was only half right: the artisan served representatives of both poles of the consumer market in Russia.: from the poorest urban people to the most demanding and affluent public who do not want to wear factory-made shoes for reasons of aesthetics, convenience, fashion and status.

Status, or, in other words, the semantic burden of shoes, is the main theme of the "Essays ...", in which the sociological meaning is consistently revealed behind each everyday or literary example. Terekhova illustrates the symbolic significance of shoes at different stages of Russian history with examples not only from literature (say, Chekhov's short stories, where unpleasant characters often wear galoshes), but also from cinema. For example, from Yakov Protazanov's Aelita, where "the luxurious shoes of the bourgeoisie are contrasted with the bast shoes and windings of peasant women," or from Andrei Konchalovsky's The Story of Asi Klyachina, where an admirer brings a gift to the villager Asa from the city — high-heeled shoes. Here the author of the book sees an allusion to the fairy-tale plot from "Evenings on a farm near Dikanka", where the blacksmith Vakula relies on the magical power of red cherries capable of melting a woman's heart.

According to Terekhova, the red shoes of the heroine of Alexey Balabanov's film "Cargo 200" are also endowed with a sacred meaning, the appearance of which the researcher calls the most powerful appearance of a pair of shoes on the Soviet/post-Soviet cinema screen. "The pumps contain the basic intercultural semantics of red shoes — danger, self—will, attraction, dating back in the Western cultural context to Hans Christian Andersen's sinister fairy tale "Red Shoes"; the specific semantics of the Soviet Union, emphasizing the exceptional value of shoes, as well as the key "nerve" of the film - pervasive fear and violence." From a household point of view, these shoes from the 2000s in the film, which takes place in 1984, are an anachronism, which director and costume designer Nadezhda Vasilyeva deliberately went for. According to the author's idea, the phrase "Uncle, I forgot my shoes — my mother's!" can only be understood by a person who lived at that time and who knew what shoes were for a Soviet woman.

The shoes from Cargo 200, which easily jumped from their time to 20 years ago, due to the semantic load, had the same "special relationship with temporality" that Terekhova writes about in the chapter on Soviet fashion discourse, drawing a dichotomy between official and everyday fashion.

In recent essays, a third alternative fashion has been added to these varieties, which appeared in the turbulent 1990s. In the final part of the book, the terminology gets stronger, and "temporality" is useful to the researcher more than once, for example, when it comes to second-hand goods. According to the author, the Russian casual fashion of the 1990s found itself at the intersection of two paradigms of attitude to things, not fully belonging to either of them. Items with an impressive Soviet past and family histories of hand-to-hand transmission were juxtaposed with new one-day items.

Nevertheless, by the end, Terekhova slightly reduces the concentration of scientific phraseology and catches a lyrical, almost sentimental wave, speaking about shoes not in a semiotic, but in a human aspect: "A simple pair of shoes can become — and is becoming — a point of intersection between the cultural history of a society, a country, the world — and the personal history of a private person. Next time in the hallway, look at your favorite old shoes with due respect."

Переведено сервисом «Яндекс Переводчик»