A Song of Ice and Fire: how Alaska became Russian

284 years ago, on July 15, 1741, Russian sailors were the first to see the southern coast of the American Mainland with the adjacent Aleutian Islands and landed on the island, which much later would receive the name of the American explorer Marcus Baker. This event is considered the date of Alaska's discovery. Izvestia recalls the milestones of the Second Kamchatka expedition.

Learn more about how the first Russian expeditions explored Alaska, how it was developed, and why it was sold to America in the Izvestia podcast.

Where was Bering sailing to

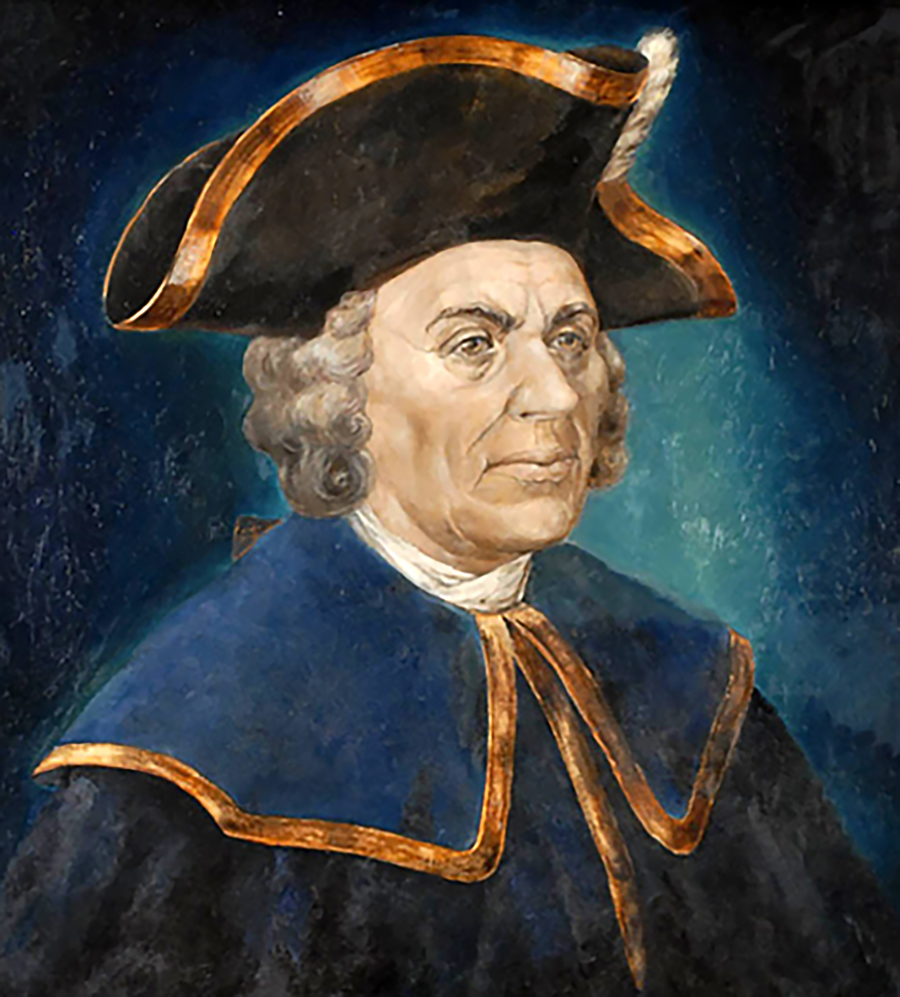

The expedition was led by Vitus Behring, an experienced navigator, a Dane in the Russian service. By the summer of 1741, they had settled in Petropavlovsk prison in Kamchatka, which they founded themselves. Behring commanded the packet "Saint Peter". His right—hand man, Captain Alexei Chirikov, one of the first brilliant graduates of the Moscow Navigation School, set sail on the St. Paul. Small high—speed brigs, 7 m wide and about 25 m long, were indispensable in the northern seas.

On June 4, the daredevils set sail from Avacha Bay with the firm intention of reaching American soil, the location of which was known only by contradictory rumor. Two weeks later, on June 19, due to heavy fog, the ships lost sight of each other and continued their dangerous voyage separately. Each of them discovered Alaska independently. Behring first tried to track down the Chirping bot. For three days, the St. Peter moved south, presumably following in the footsteps of Captain Chirikov. But then, having lost hope of finding a companion, Bering decided to turn northeast and soon crossed the central waters of the Gulf of Alaska for the first time.

This maneuver of the commander went down in the history of geographical discoveries. Three weeks later, on July 15, Bering clearly saw the outlines of the big shore, which he had been striving for for many years. It was Alaska. The sailors saw the mountains of St. Elijah, the southern coast of the peninsula.

Behring immediately assembled a team and declared the open land to be Russian. The captain-commander was weakened during the journey, suffered from illness, but ordered the Russian flag to be hoisted high and served a solemn prayer service on board the St. Peter. The weathered sea wolves looked proudly towards the "mother earth": they managed to fulfill the long-held dream of Russian explorers, to find a continent about which previously only vague legends circulated.

After that, the St. Peter approached the uninhabited Kayak Island and landed on its shore, mainly to replenish fresh water supplies. However, Bering named this island after the prophet Elijah, and Lieutenant Ivan Starichev named it Kayak much later, in 1826.

The sailors suffered from scurvy and struggled to withstand the rigors of the voyage. Sofron Khitrov's boat with 15 rowers was the first to dock on the island. They poured out onto the shore without hesitation, feeling the ground under their feet for the first time in many days. The famous naturalist, associate professor Georg Steller, who was responsible for scientific research in the expedition, wandered tirelessly around the island for 10 hours, studying its landscape and flora. He managed to describe 160 species of plants and complained that Bering had given him too little time to explore the island of St. Elijah...

After a short stop, Bering headed west along the coast. Along the way, the sailors from the St. Peter discovered the Evdokaevsky Islands, the Aleutian Ridge in Alaska, and on one of the islands our sailors first met with the Aleuts, who for a long time will become the main allies of the Russians in Alaska. The meeting, fortunately, was peaceful, except for a small incident. One of Bering's associates treated the most sociable Aleut to a glass of vodka. He spat out "firewater" in horror, and then spent a long time telling his colleagues about his feelings from a strange, obviously magical drink. This island got its name in honor of the sailor Nikita Shumagin, the first participant of the legendary expedition, who died of scurvy and was buried on this land. Bering named one of the islands after Chirikov, for whose fate he was worried.

Bering wanted to spend the winter in Russia, but the great traveler failed to return to Kamchatka. In the fall, the St. Peter almost lost control. Bering managed to approach one of the islands, which in the future will be named Commander's Islands in his honor. On this island, the sailors began to prepare for wintering. But scurvy was wearing down the team: fewer than five dozen of them remained out of 75. Captain-Commander Vitus Behring himself died on December 6, 1741.

How Chirikov discovered America

Captain Chirikov's voyage began much more dramatically, but it ended much more successfully. It was he who managed to reach the coast of Alaska on July 15, two days before Bering. "Saint Paul" approached the island, which nowadays bears the name of Baker. Chirikov sent a dozen and a half men ashore in two boats. Alas, they apparently died in skirmishes with the locals. Or maybe someone stayed to live among the aborigines. Chirikov waited a long time for his companions, but did not dare to dock on the island. The St. Paul stayed off the coast of America for two weeks, and then turned back.

Heading to the Aleutian Chain, Chirikov and his sailors discovered several more islands, among them Agatta, Alakh, Umnakh. Each of them was independently mapped by the captain. In October, the heroes returned to Petropavlovsk. They managed to avoid severe storms and safely docked at their native harbor. The entire trek from present-day Petropavlovsk to the coast of Alaska and back was about 9 thousand km. And this is in conditions when every mile was given with blood. Chirikov, losing his strength, encouraged his brave men.

Already in Petropavlovsk, in his report, Chirikov, who suffered from exhaustion and tuberculosis, claimed: "In the northern latitude at 55° 35 minutes, we received land, which we recognize without a doubt that it is part of America."

He justly got the honor of the discoverer of Alaska. After this feat, Chirikov lived for about seven more years. He ended his days at the age of 44, being the head of the Moscow office of the Admiralty Board. The same island in the Pacific Ocean, off the coast of Alaska, still bears his name forever. His achievements delighted our great educator Mikhail Lomonosov, who insisted that it was Chirikov who went further than others and was the first, and argued that the memory of this achievement was "necessary for our honor." Lomonosov was not mistaken, this is the historical truth.

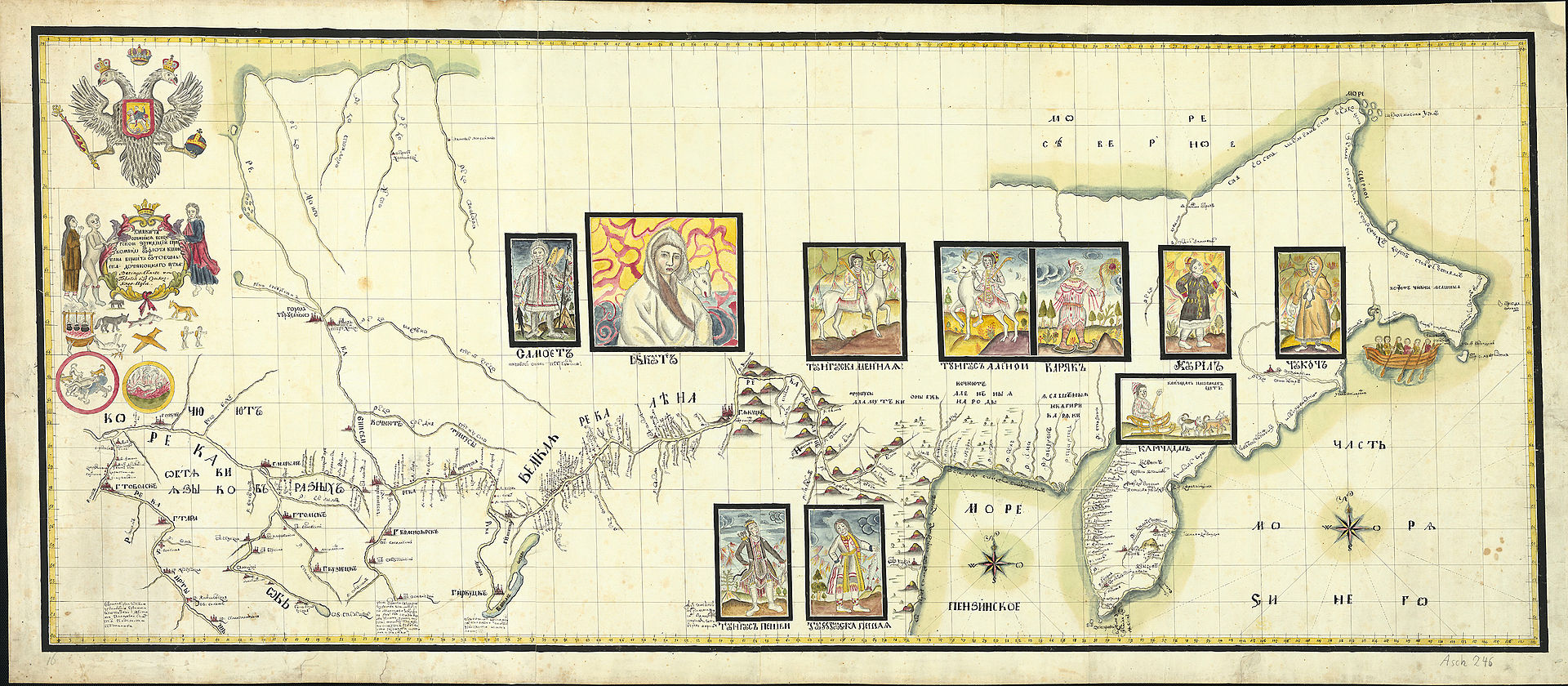

Who tried to reach Alaska before Bering

Of course, attempts to find a Large land on the border of Asia and North America have been made before. Getting there on ships, boats, and dogs in the 17th and 18th centuries was an incredibly difficult task. Perhaps the first European to see the Alaskan land was the glorious Cossack pioneer Semyon Dezhnev. In 1648, he reached the strait separating Chukotka from Alaska. And, according to one version, the storm carried him to American soil. This was the first, as yet unconscious, Russian breakthrough to Alaska. But Dezhnev's rather detailed petition had been gathering dust for many years in the Yakut voivodeship, it was not known either in Moscow or in St. Petersburg, or even more so in the West. Therefore, Bering and Chirikov had to reopen the strait, essentially. At the same time, their priority in the scientific description of the islands and coasts of Alaska is indisputable.

However, we rarely remember that hundreds of Russian citizens had already visited Alaska by that time and even fought with the local natives, taking boats to the American shores. They fought for nomads, for deer, for new shores for fishing. Some aborigines of Russian Asia remained in Alaska. By that time, Russian researchers had received vague information about the far coast from the Chukchi and Evenk leaders. The enmity between the Chukchi and the Alaskan Eskimos flared up from time to time later.

One day, Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz asked Peter the Great: "Where is the limit of your empire? Where does Eurasia end and America begin? Is there a land border between the continents?" Peter, who respected the great scientist, was embarrassed. Russian Russian Emperor Shortly before his death, in December 1724, the first Russian emperor drew up detailed instructions for the First Russian Kamchatka Expedition. It was a unique enterprise. For the first time, the state so carefully prepared a long-range cast of explorers. The First Kamchatka expedition was led by the same Vitus Bering. Young Chirikov went camping with him. They made several voyages from the coast of Kamchatka, but they did not manage to reach the American shores then.

For Europeans, Alaska remained a mysterious land: either a peninsula to the mainland, or an archipelago, or even a mirage. But both Bering and Chirikov understood that, despite the most serious climatic difficulties, they had to look in that direction.

Finally, in the summer of 1732, captain Ivan Fedotov and surveyor Mikhail Gvozdev equipped and made a daring dash to the shores of Alaska on the ship St. Gabriel. The experienced navigator Fedorov was ill, and responsibility for the voyage fell mainly on Gvozdev's shoulders. An important role in the team was played by Arkhangelsk Pomeranian Kondraty Moshkov, a hereditary sailor, an experienced helmsman who had been through many alterations. Four sailors, more than 30 armed servicemen and interpreter Egor Buslaev, who knew the Chukchi language, set off with them. Fedorov and Gvozdev understood that the trip could turn into an attack on the ship, and they thoroughly prepared for defense.

They set sail from the mouth of the Kamchatka River, crossed the Bering Strait, and replenished fresh water supplies near Cape Dezhnev. From there, we headed East and saw land in the area of the current Cape Prince of Wales. Gvozdev reported: "On August 21, in the afternoon, at 3 a.m., the wind began to blow, the anchor was lifted, the sails were lowered and went to the Mainland, and they came to this land, anchored." They did not land on American soil, but they saw it clearly and recorded a lot. Of course, Gvozdev's journey was an important stage in the development of Russian America: it was then that the Europeans received the first information about Alaska. These sailors became the forerunners of Bering, Chirikov and their discoveries.

Why Alaska had to be sold

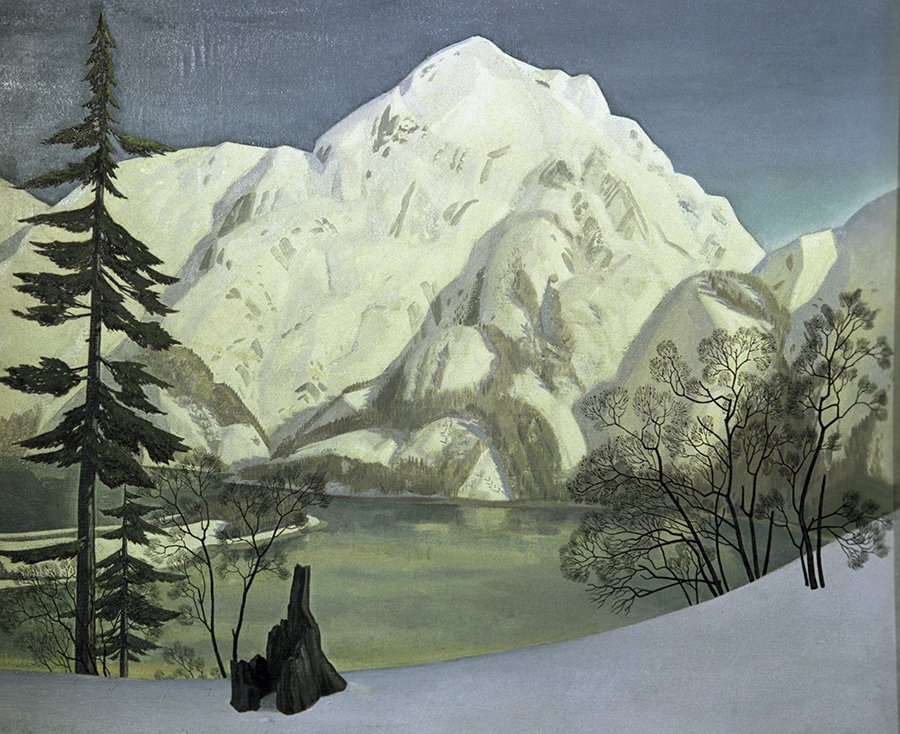

The achievements of Chirikov, Bering, Gvozdev and Fedorov were not in vain, their discoveries remained not only on the pages of geography textbooks. By the end of the 18th century, Alaska had become part of the Russian Empire, both on paper and in practice.

Full-fledged, widespread development of the snow-covered peninsula began in the 1770s. The words of a popular song in which the great Empress is reproached for the loss of the peninsula are extremely unfair: "Catherine, you were wrong!" It was during Catherine's time that Alaska became a real Russian land. Outposts of the empire and Cossack settlements appeared there, meteorological and geographical studies were conducted there, Russian researchers and warriors studied the locals there, participated in fishing with them, and sometimes repelled attacks by aggressive Indian tribes.

A significant milestone in the history of Alaska was the establishment of the first Russian settlement on the peninsula, Unalaska, in the Aleutian Archipelago, in the 1770s. In 1784, the expedition of the "Russian Columbus" Grigory Shelekhov arrived on the island with the Eskimo name Kodiak. Many aborigines of the peninsula converted to the Orthodox faith. And in 1783, the American Orthodox Diocese arose. And all this happened under Catherine, who, apparently, was right after all. In 1797, on Shelekhov's initiative, preparations began for the creation of a powerful monopoly company that could take over trade and fishing in Alaska and its surroundings. It was established in 1799.

The heyday of this monopoly was impressive, but it did not last long. On October 18, 1867, by the decision of Emperor Alexander II, St. Petersburg ceded Alaska (or rather, the whole of "Russian America") The North American United States. At that time, it was considered unprofitable to develop such a remote and almost deserted territory, and the sale was considered a rational decision. But the memory of the discoverers, who essentially gave their lives to uncover the Alaskan mystery, cannot be erased from history. They were the first. Lomonosov's formula cannot be undone: knowledge of this is "necessary for our honor."

The author is the deputy editor—in-chief of the magazine "Historian"

Переведено сервисом «Яндекс Переводчик»